Before we had refrigerators, ice machines and air conditioners, we depended upon frozen lakes and rivers to cool us year-round.

Before refrigeration, how did area residents and businesses chill beverages and perishable foods to prevent spoilage? And prior to air conditioning, how did people cool indoor air on sizzling summer days?

Like other Americans from the mid-1800s to the early 20th century, they used blocks of ice that were harvested, or cut, from frozen lakes, rivers and ponds. Businesses from meat packing plants and dairies to breweries and movie theaters used ice to preserve products or cool the indoor air. At home, a common sight was the ice box: a freestanding, upright cabinet that used an ice block to keep items cool.

While civilizations have used ice or snow to preserve food and drink for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, harvesting ice from frozen waterways seems to originate with Boston merchant Frederic Tudor. In 1805, he sent a shipload of ice to the Caribbean island of Martinique to help hospital patients suffering from yellow fever, according to an 1888 U.S. Department of the Interior report on ice harvesting. Tudor’s idea spread westward, and decades later, when a young Chicago grew in population, so did the demand for ice.

In the cold winters of the late 1800s and early 1900s, inland lakes and rivers in northern Illinois and Wisconsin became “farms” producing ice for Chicago-area homes and businesses.

“Similar to corn or wheat, ice was viewed as a crop,” says David Siegenthaler, volunteer researcher at the Elgin History Museum. “Newspaper accounts often referred to a ‘good crop’ if there were abundant cold days, or a ‘bad crop’ if the winter was warmer than normal.”

Harvesting was a common site on Crystal Lake in McHenry County, the Fox River’s Chain o’ Lakes and other sites in Lake County. Additionally, harvesting in southern Wisconsin was common on Geneva Lake and Walworth County, Kenosha County, and Milwaukee- and Madison-area lakes.

Lake Michigan, however, was not an option for ice harvesting. Its water was “impure” and its frequent movement made for slushy, porous ice, according to the Feb. 26, 1893, report in the Chicago Daily Tribune.

On Crystal Lake in McHenry County, ice harvesting “was an extremely important, major industry from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s,” says Diana Kenney, president of the Crystal Lake Historical Society. The city’s namesake lake was chosen because of its reputation for clear, clean water. When a railroad line came to town in the 1850s, it ushered in an era of ice harvesting on the lake. In 1856, entrepreneur Amos Page ran the first commercial ice business called the Crystal Lake Ice Co., according to the historical society’s records. To ship the ice, Page constructed a railroad track from the lake to the downtown depot, along today’s Dole Avenue. Four years later, another company, Joy & Frisbie, gained access to the lake, shipping 10,800 tons of ice to Chicago annually. By 1875, Crystal Lake had 12 ice houses, mostly along the south shore. A year later, 1,200 train carloads of ice were shipped to Chicago, according to local historical society records.

The Fox River had dozens of ice companies from Cary to Elgin, all the way down to Ottawa, according to newspaper accounts from the era. In Ottawa, ice was harvested from the man-made Illinois and Michigan Canal, which ran through the city’s downtown as part of the canal’s 96-mile journey linking Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, according to Dan Schott, docent at Ottawa’s Historical and Scouting Heritage Museum.

There were 12 ice firms in Elgin by 1888, with the average employee making $1.25 per day, according to the Elgin Daily News on Jan. 7, 1888. The following season, Knickerbocker Ice Co. – one of the area’s largest – and other Elgin-area companies harvested, collectively, some 33,000 tons of river ice, according to the newspaper.

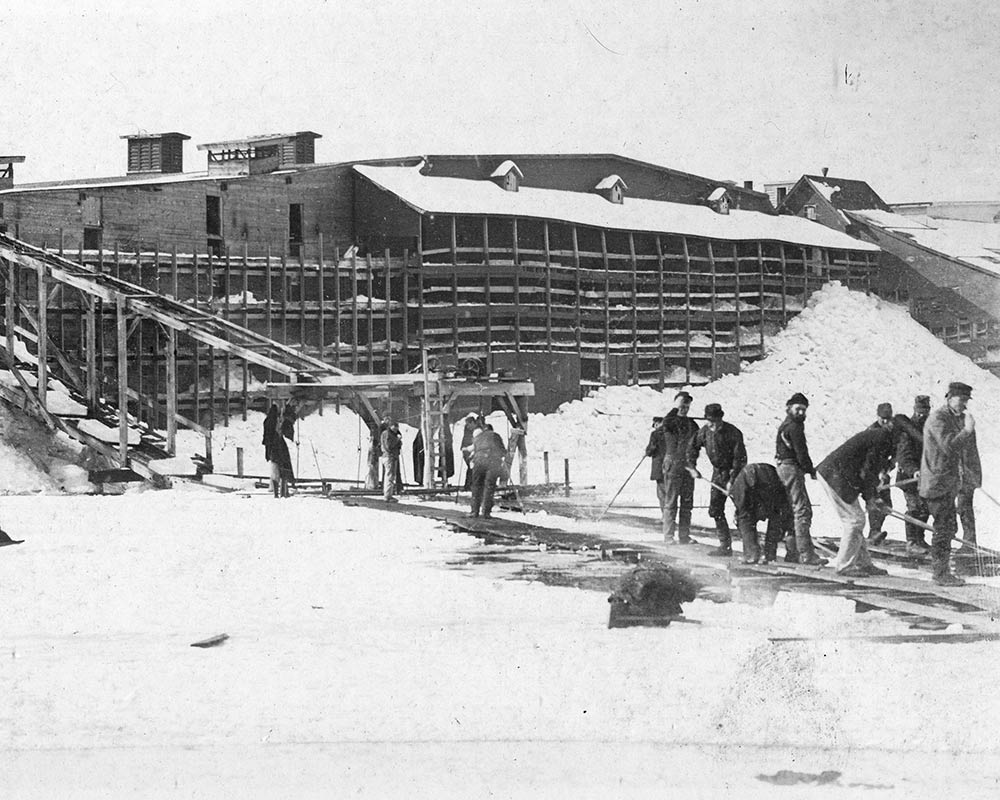

A typical harvesting season began in late December or early January and continued until mid- to late February. At peak season on Crystal Lake, the work required about 225 workers. Companies on the Fox River typically employed, individually, anywhere from 35 to 200 workers per season, newspapers report.

“Workers ranged from local farmers looking for off-season income to transients who would take the train from Chicago and stay in bunkhouses built by the ice companies,” says Craig Pfannkuche, a retired history teacher and currently a historian at the Union-based McHenry County Historical Society.

With spectators often watching from shore, workers typically harvested ice in several steps. First, they made sure the ice was at least 6 inches thick. Ice typically froze to 12 to 20 inches or more on rivers and lakes. They used a horse-drawn plow blade to scrape away the snow, which was pushed or carried out of the way. Some operators had an alternative: They used long-handled chisels to cut holes in the ice every 6 to 10 feet, allowing the water to come up and saturate the snow, which then converted it into ice.

Next, they used a plow to cut a grid of guidelines across the ice field, usually 22 inches apart to create square ice blocks, known as “cakes.” Then, following the guidelines, they plowed about two-thirds of the way through the ice. Workers often packed snow into the deep grooves to prevent water from seeping into the cracks and re-uniting the ice cakes.

After scraping the ice one more time to remove ice shavings, workers typically used large-toothed hand saws of 4 to 6 feet to cut the ice into “rafts” or “floats,” which typically were two cakes wide and 10 cakes long.

With long metal poles, they pushed the rafts through a previously cut canal toward the ice house on shore. Other workers broke apart the rafts into individual cakes using large, fork-shaped tools.

On shore, workers pushed the ice cakes under a planer to ensure uniform thickness. Then, they pushed each cake onto a ramp, where the block was caught by tongs and chains and pulled up to the ice house. The chain was guided by a pulley system powered by horses, and, later, engines.

Ice houses in this region could be 75 feet high and at least 200 feet long. Workers inside coated each block with sawdust or straw to keep the blocks from freezing to each other when stacked together. The dry matter also preserved the ice well into the high-demand summer months.

Cakes were loaded into train cars and shipped to clients like Chicago’s Armour & Co. meat processors or the Bowman Dairy Co. in Crystal Lake. Early Chicago movie theaters, including the Biograph, used ice blocks to cool the inside air during the summer, Pfannkuche says.

Ice blocks also made their way to individual residences via horse-drawn wagons and later, trucks.

Ice companies gave each customer a cardboard sign to place in the front window. Customers could rotate its position to show one of four numbers – 25, 50, 75 or 100 pounds – indicating how much ice they wanted for the coming week. The delivery driver (known as an ice man) used large metal tongs to lift each block, carry it on his shoulder – cushioned with a blanket or leather padding – and head into the house to stock the customer’s ice box. Once the block began to melt, emptying an ice box’s drip pan was a common household chore. Ice delivery was a welcome sight for many.

“On sweltering summer days, before air conditioning, it wasn’t uncommon for children to hang around an ice delivery truck, hoping to get a few spare ice fragments to lick or rub on their faces,” Pfannkuche says.

This business was demanding and often dangerous. Besides the bitter cold, there was the danger of slipping on the ice and breaking a leg or falling into the frigid water. Workers inside the ice house had to guard against injuries or falls from scaffolding or stacked ice cakes.

In 1900, the only ice-harvesting death in Crystal Lake occurred when a man was caught in the rotating chain of a ramp, says Kenney.

A decade later, the July 31, 1912 edition of the Elgin Daily News reported: “Struck in the side by a heavy iron bar, William Demien, an employee of the Knickerbocker Ice Company, was seriously injured this morning. He was unloading ice and lifting it by means of a hoist. When the piece broke loose, the lever struck him with a crushing blow. Two ribs were broken and he suffered internal injuries. Three hundred pounds of ice crashed to the ground, swerving the bar with equal force.”

Horses weren’t immune to dangers, either. Though they were fitted with cleated horseshoes, to improve their traction, Pfannkuche says, a horse sometimes would slip and fall. A newspaper account from the Jan. 23, 1936, Crystal Lake Herald mentioned a horse falling into the water.

Workers hitched up a second horse on the ice to pull out its unfortunate cohort.

The typical ice house was a fire hazard, as it usually was insulated by a double wall filled with sawdust, Siegenthaler says. In Elgin, fire destroyed the Dundee Ice Company’s ice house in August 1914. Several ice houses burned down on Crystal Lake, Kenney adds.

Beyond the cold and the physical challenges, there was the emotional pressure to work quickly and maximize output. The weather often was inconsistent in a season that lasted typically four to six weeks, Pfannkuche says.

Warm winters that didn’t produce adequate ice along the Fox River forced some companies to import cakes from Geneva Lake and other places in Wisconsin.

Ice companies on Crystal Lake and the Fox River – citing low profits – formed trusts that created monopolies. This angered customers. In Elgin, the trust formed by the Consumers Ice Co. resulted in two local investors re-organizing the once-defunct Elgin Ice Co. to restore competition. This led to a heated battle between the two companies over harvesting rights. In January 1915, a judge denied a request by the Consumers Ice Co. to restrain Elgin Ice Co. from shipping ice through what Consumers claimed was its own field on the Fox River.

“In making his ruling, Judge Slusser emphasized two points: That the Consumers company was not sufficiently damaged to entitle them to an injunction, and that the Fox River is a navigable stream open to the public for pleasure or profit,” reported the Jan. 7, 1915, edition of the Elgin Daily Courier.

Entrepreneurs and workers alike accepted the challenges of providing Chicago a frozen commodity.

After all, ice reduced the need to salt, pickle, or store perishable food and drinks in root cellars.

“It’s pretty amazing when you think of danger the men were subjected to,” Kenney says. “Yet the work was vital, and it was something you did because you needed the money.”

By the turn of the 20th century, manufacturers found ways to make their own ice without the need to harvest it from area waterways, writes author Jonathan Rees in his book, “Before the Refrigerator: How We Used to Get Ice.” Artificial ice was superior in just about every way because it was cleaner, colder and easier to produce.

Starting in the 1920s, electric refrigerators began to replace household iceboxes.

“Some rural sections of the country lacked a reliable electric grid even after World War II,” Reese writes. “Nevertheless, once the effectiveness of refrigerators improved and their prices dropped, the ice industry (in its 19th century form), gradually disappeared.”

By the late 1950s, harvesting the “winter crop” would exist only in memory.