Check out these destinations that reflect the genuine character of our region.

Campana Factory

901 N. Batavia Ave., Batavia

Ernest Morgan Oswalt established the Campana Italian Balm company in 1926, and despite the arrival of the Great Depression three years later, his lotion rose to prominence on the strength of Oswalt’s innovative marketing strategies. Not only did he offer more than 1 million free samples in magazines but he also created a radio show to promote his products.

By 1936, the company was America’s premier hand lotion brand.

The company’s rapid rise to fame required a new production center, and Oswalt brought his vision for a state-of-the-art factory and corporate headquarters to a quiet place between Batavia and Geneva. The distinctive Campana Factory, built in 1936, became an Oz-like marvel combining the Bauhaus and Art Deco styles. The factory’s horizontal three-story structure, anchored by a tower at its center, features buff-colored tiles and glass block windows, with accents of seafoam green. Aluminum entrance doors, surrounded by a black glass, feature a design of interlocking rectangles.

The 100-meter tower stretches to the sky with raised bands of tile and glass blocks, whose presence helped to maximize interior illumination.

Inside, the factory pioneered the use of complete air conditioning, an innovative pool of secretaries, and manufacturing technologies such as a gravity-fed rotating mixing system that simultaneously supported six stages of the cosmetic preparation process.

During World War II, Campana changed the name of its Italian Balm due to anti-Italian sentiments. The company and its distinct factory were acquired by laundry detergent brand Purex in the 1960s. Campana stopped production in 1982.

Today, the factory still bears Campana signage, though it’s now home to several businesses including a costume and makeup product company, a furniture store and a chiropractor.

Powers-Walker House

Ill. Rt. 31 and Harts Road, Ringwood, (815) 338-6223, mccdistrict.org

Elon and Mary Powers ventured westward with their five children in 1845 and built a log cabin near a bubbling spring amidst the vast prairies of northern McHenry County.

As their family continued to grow, they constructed a Greek Revival-style house in 1854. Nine years later, they sold it to their neighbor, Samuel Walker. The Weidrich family then transformed the surrounding land into a bustling dairy farm in the early 1900s.

Electricity brought modern conveniences to the region in 1953 and the surrounding land eventually became a private residence and a corporate hunt club and lodge. The Powers-Walker House remained largely unchanged through the generations.

The Weidrich family bequeathed their farm to the McHenry County Conservation District in 1975, and 20 years later an effort began to restore the house, some sections of which were still in good condition.

Today, the fully restored home hosts public programs and events amidst the 3,400 acres of prairies, savannas and floodplain at Glacial Park.

Public programs at the home, hosted by the McHenry County Conservation District, take people back in time to see the families that once called this place home.

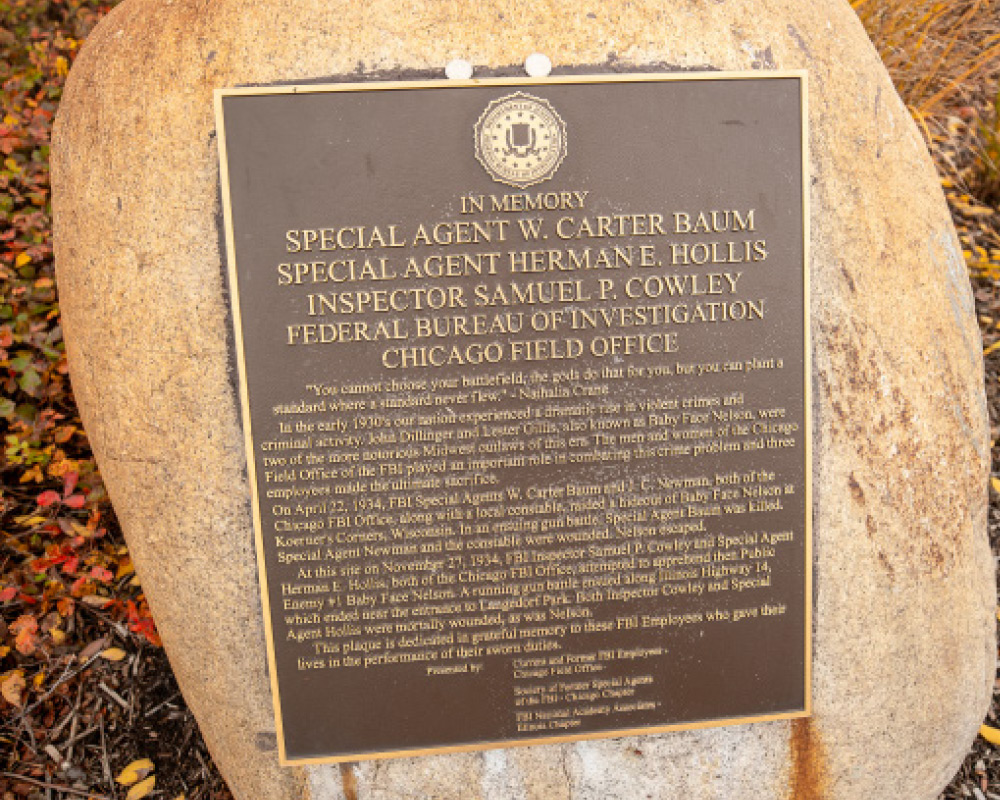

Battle of Barrington Memorial Plaque

Langendorf Park, 235 Lions Dr., Barrington

Chicago’s gangsters made a habit of hiding out in Wisconsin. Such was the case for notorious bank robber and gangster George “Baby Face” Nelson, who killed an FBI agent following a raid at the Little Bohemia Lodge in April 1934.

Nelson, his wife, Helen, and his sidekick, John Chase, had been with John Dillinger’s crew at the Little Bohemia, and they reunited to help him rob a bank in South Bend, Ind., that June. The Nelsons and Chase traveled to California, Nevada, New York and Chicago that summer, eventually stealing a car in Chicago and heading back to Wisconsin.

It was on a trip back to the city in November when FBI agents noticed the trio in Wisconsin. They’d made Nelson a high-profile target since Dillinger’s death that June. The 25-year-old Nelson fired on the car of one pair of agents before another team, Sam Cowley and Herman “Ed” Hollis, were on the trail, the latter having played a role in the demise of Dillinger at the Biograph Theatre.

The chase proceeded down what’s now U.S. Route 14 until Nelson pulled into a park just outside Barrington and prepared to ambush the agents. In the ensuing shootout, Cowley and Hollis both hit Nelson, who returned fire and fatally wounded both agents.

The trio of gangsters drove away, but by that evening Nelson had died from his injuries. An anonymous tip led FBI agents to his lifeless body in a ditch near a cemetery in Niles Center, what’s now Skokie.

Today, a plaque outside the Barrington swimming pool pays memory to the FBI agents who lost their lives in what’s been dubbed “The Battle of Barrington.”