New, expecting and soon-to-be-expecting moms are full of questions. For local physicians, that’s why a health care partner is an essential part of the journey.

A baby is a miracle, one that expecting mothers can protect before, during and even after the baby makes its appearance.

If you’re planning to start or expand a family, the first thing to do is meet with your gynecologist, says Dr. Kelli Kilgore, an OB-GYN at Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital in Barrington.

From there, you’ll be in good hands to learn everything you need to know about growing a healthy baby.

The Journey to Pregnancy

Even before you conceive, there are steps you can take to make sure your pregnancy is as safe as possible. Start with a prenatal vitamin and appropriate diet and exercise.

“And if you have any medical comorbidities, get those under control or know how to manage them,” says Kilgore.

If you have high blood pressure, make sure it’s optimally controlled; if you’re diabetic, make sure your A1C blood test is appropriate; and if you’re obese, work on weight loss and healthy lifestyle changes, she says.

It’s also a good idea for both parents to go through prenatal genetic screening tests to see if either parent is a carrier for any autosomal recessive diseases such as cystic fibrosis or spinal muscular atrophy.

And make sure you’re up to date on your immunizations. Some vaccines – like those for rubella (German measles) or chicken pox – cannot be taken while you’re pregnant or trying to get pregnant, Kilgore says.

If you’ve become pregnant unexpectedly or didn’t see your OB-GYN before conceiving, don’t worry. You’re not alone. Most women – probably 80% or more – are seen by an OB-GYN for the first time during the first trimester, Kilgore says.

“Appointment by appointment, there is a lot of counseling about pregnancy precautions, travel, medications and reviewing your risk factors,” Kilgore says. “Aside from that, every visit is pretty much going over the expectations for that gestational age.”

While a lot of that information may seem self-explanatory for seasoned mothers, there are a lot of questions for first-time moms.

“No. 1 I hear all the time is, ‘Can I eat lunchmeat?’” Kilgore laughs. “Yes, you can, as long as you’re not buying it from a gas station.”

Meeting repeatedly with your OB-GYN is more exciting today than in decades past, simply because medicine has come a long way.

OB-GYNs now can offer earlier screenings to reveal gender or detect genetic complications like Down syndrome. It’s important to go over these options with your provider, Kilgore says, and it’s even more important to follow through with the more crucial screenings, as well.

“There are several different things throughout pregnancy we do to make sure everything is safe in pregnancy,” Kilgore says. “There’s a lot of blood work to make sure we know things like what your Rh factor is: Rh positive or Rh negative. If you’re Rh negative, you need to get a certain shot to make sure you don’t develop antibodies against the baby.”

Once expecting mothers get closer to their third trimester, it’s time to start thinking about a birth plan.

Kilgore says Good Shepherd Hospital promotes vaginal births as much as possible, but mothers need to understand that C-sections are sometimes necessary.

Going over pain management is important.

“Labor is not easy,” Kilgore says. “We have a lot of patients who are coming in and want a more natural plan and would prefer to not have an epidural. We need to have that plan in place to know how you’re going to do with the pain.”

Some hospitals offer nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, which is a very short-acting pain reliever. There’s also the option of pain medication by IV.

“We can only do that up to a point in your progression,” Kilgore says. “The baby is exposed to that IV medication, so they can have difficulty breathing after birth because they have pain medication as well. An epidural is a constant infusion over your spinal cord that is not seen by baby.”

Some women will manage to push past all of the pain of labor without any pain management aids until it comes to the final pushes.

“If you prefer not to have Pitocin or augmentation of labor, we’re willing to work with that,” Kilgore says. “If you’ve been in labor for 40-plus hours, we would strongly encourage augmenting with Pitocin to help you reach a successful vaginal delivery, but there’s always patient autonomy. It is also our job to make sure everybody is safe.”

Post-Birth Support

During pregnancy, most hospitals offer classes to help parents prepare. Once the baby has arrived, there are still many resources to help women ease into their new roles as mothers.

“I think people have a hard time understanding how challenging breastfeeding is,” Kilgore says. “It seems like it will be natural, but it can be very challenging for first-time moms, and there can be a lot of issues with postpartum depression because of those struggles.”

Nurses can help new mothers with proper latching techniques, but hospitals also have lactation consultants who are specifically trained to help with breastfeeding struggles. At most hospitals, these experts are available every day.

“And not just when mothers are at the hospital. Once they go home, the hospital has Baby Bistro, [a breastfeeding support group] where they can come once a week and meet with other new moms,” Kilgore says. “For as long as you need, you can just show up for support from our lactation consultants or make a one-on-one appointment with them.”

One post-pregnancy issue that always needs to be addressed is the potential for postpartum depression.

Those who are at an increased risk of falling into postpartum depression include those who already had mental health issues before becoming pregnant, and sometimes those who tend not to have a lot of support, Kilgore says. Doctors now recommend a follow-up with mothers after two weeks.

“I usually tell people if they’re crying more often than not, I want them to reach out,” Kilgore says. “If they feel like they’re not adjusting well to motherhood, even if it’s not their first time, or not bonding well with the baby, reach out. We go through a lot of this at two weeks, and [new moms] fill out a depression questionnaire at six weeks, as well.”

If you feel you may have postpartum depression, talk with any of your doctors, Kilgore says. She also has a “massive list” of online resources, because she understands “it’s really hard to get places when you have a newborn.”

“You can start medication or counseling to get things under control,” she adds. “Your OB can do that, and your primary care doctor or pediatrician can talk to you about how to get started.”

It’s also important to remember your OB-GYN doesn’t cease being your doctor as soon as you’ve had your baby.

“Many people think your OB care ends at birth – that’s a common misconception,” Kilgore says. “There are lot of resources at Good Shepherd through that first year.

“There is not a question that is ever too stupid to ask your OB-GYN, ever,” she adds. “Most of the time, 100 other people have had that exact same question.”

Protecting a Woman’s Options

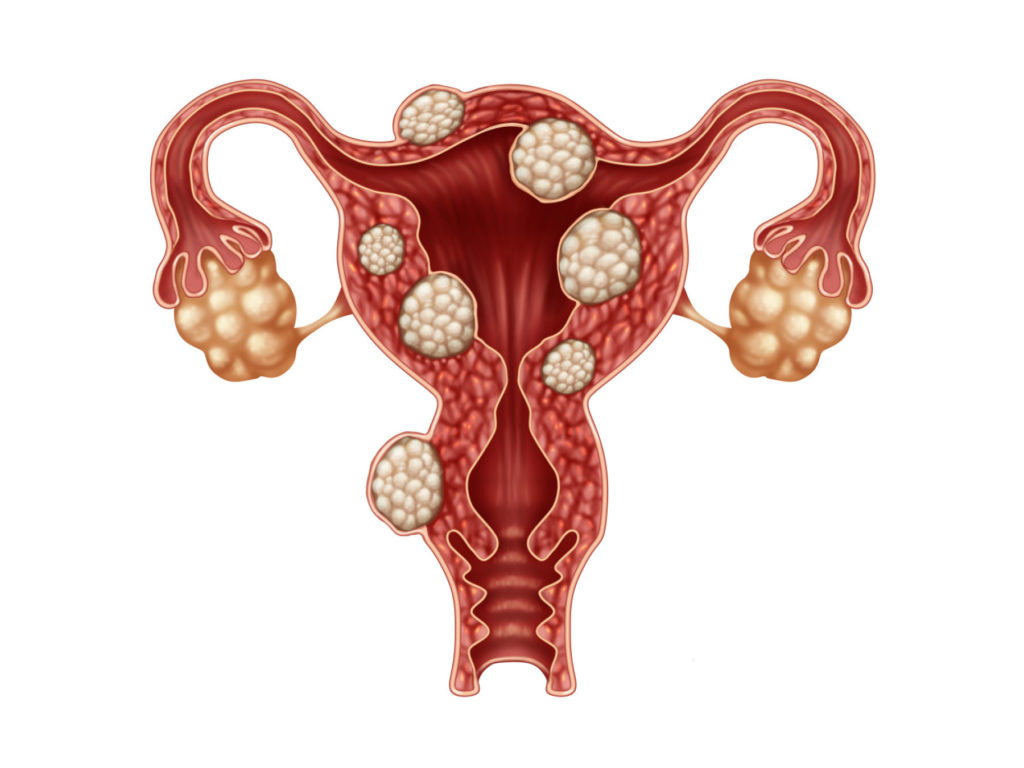

About five years ago, Dr. Meredith Martin-Johnston, OB-GYN at Ascension Saint Alexius in Hoffman Estates, was working with a patient who had a fibroid – a tumor, usually benign, that develops in the uterus.

Martin-Johnson presented her patient with treatment options, which at the time included a hysterectomy – a surgical procedure that removes part or all of the uterus – or a myomectomy – a less-invasive operation that cuts away fibroids without removing the uterus.

The patient instead sought alternative options at Mayo Clinic, where she found they offered radiofrequency fibroid ablation.

“I had never even heard about it,” Martin-Johnson recalls. “I started doing some research on it, and it took me a little while to get all my ducks in a row, but I went out to California to watch a few cases in the Los Angeles area. I’ve been doing them basically since the spring.”

Martin-Johnson and Ascension Saint Alexius now offer Acessa, a laparoscopic radiofrequency fibroid ablation procedure, which is considered even less invasive than a myomectomy.

Through Acessa, Martin-Johnson makes two small incisions in the abdomen, places a needle-like probe into the fibroid and destroys it by heating it, Martin-Johnson says.

“We’re causing less injury to the uterus, and the fibroid starts shrinking immediately during surgery because I can see it,” she says. “And it continues to shrink during the 12 months after the surgery.”

Usually, the removal of fibroids causes major blood loss because significant portions of uterine tissue are removed via cutting and suturing, Martin-Johnston says.

With Acessa, there is less trauma to the uterus, and therefore minimal to no blood loss, she says. Plus, there are minimal adhesions – bands of scar-like tissue that cause two surfaces inside the body to stick together.

Acessa was created in 1999 by Dr. Bruce Lee, an OB-GYN in California, Martin-Johnston says. However, it wasn’t highly marketed, and was usually only available in bigger cities.

That’s one of the reasons Martin-Johnston decided to learn the procedure, so she could bring it to the Chicago suburbs. That, and the fact that fibroids are present in up to half of all women – more so in certain populations.

“There’s a ton of patients who come to me who want a uterine-sparing procedure … and usually I would tell them there was hysterectomy or myomectomy … and those are actually more difficult now,” she says.

After an Acessa procedure, patients usually return to work four or five days later, Martin-Johnston says. The procedure itself doesn’t take much time: patients typically spend between four and six hours in the hospital, and they’re released the same day.

“Everybody has been doing great,” she says of her Acessa patients. “They have significant relief of their pressure feeling and pain, and bleeding has been much less. I love being able to offer it.”

How does all of this relate to childbirth?

First, one of the previous options of fibroid removal – a hysterectomy – would eliminate a woman’s chance of ever getting pregnant.

But even after a myomectomy, which still leaves women the chance to get pregnant, the C-section rate is much higher, depending on how high the fibroid was in the uterine cavity, Martin-Johnston says.

“Women who have gotten pregnant after Acessa tend to have more natural labor and delivery,” she adds. “There have been a number of successful pregnancies after Acessa procedures.”

Additionally, hormones during pregnancy can trigger the growth of fibroids, which could necessitate their removal.

“Fibroids can enlarge during pregnancy because of the hormonal support needed during pregnancy,” Martin-Johnston says. “Acessa is a way to treat these fibroid tumors with a uterine-sparing procedure that causes the least amount of damage to the uterus.”

The Impact of Breastmilk

In late February, Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital rolled out a donor breastmilk program for babies in the hospital’s special care nursery.

Just months later, the program had already expanded.

“The success was pretty great,” says Pamela Chay, program manager of maternity services at Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital. “By the end of June, we were able to roll it out to our mother-baby units. So, not only were our most fragile babies able to receive donor milk, but now any of our babies can receive it.”

Most people know there are significant health benefits for an infant who receives breastmilk, and there are benefits to the woman who provides the breastmilk, says Chay.

In fact, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests mothers exclusively use breastmilk for the baby’s first six months, and even once solid foods are introduced, mothers are encouraged to breastfeed for two years or longer.

But not every mother is able or willing to breastfeed. For those mothers, donor milk programs can help.

“If the mother has her own milk, that’s the holy grail,” Chay says. “But if they don’t have enough volume or don’t have enough milk or if baby needs a supplement, then donor milk is a really good option to bridge that gap between birth and when the mother has enough milk to give her own baby.”

If a mother chooses not to breastfeed and her baby is in the special care unit, providers try to use donated milk as much as they can.

“We give donor milk because babies are more fragile, and we want to line the babies’ gut and microbiome and give the babies some immune factors that maybe they didn’t get because they were born early,” Chay says. “We try to delay the amount of formula because formula doesn’t provide the health benefits received from breastmilk.”

There are components in both the mother’s milk and a donor’s milk that help the baby have a healthy start, Chay says. Formula certainly has its place, but there is no downside of using donor milk.

“It is just packed full of nutrients the baby wouldn’t get if their mom wasn’t able to breastfeed, including antibodies, lactoferrin, lysosomes, growth factors, oligosaccharides, gangliosides and more,” she says.

“I would sum it up as: these properties are bioactive factors to help the baby fight infection and to coat the lining of their intestines to set the baby up for a healthy start,” Chay adds.

Many hospitals have donor milk programs for their special care units. It’s rarer for donor milk to be available for mother-baby units, Chay says, but even if you don’t deliver at a hospital with those programs, there are other options.

Parents can buy 10 bottles of donor milk without a doctor’s order from local milk dispensaries, she says.

Mother’s Milk Bank of the Western Great Lakes works with Northwestern Medicine Lake Forest Hospital, and it’s a great resource for mothers looking for a local milk depot, Chay says. Donors are also needed. To learn more, visit milkbankwgl.org.

“For families who have experienced a pregnancy or infant loss, milk donation is an option,” Chay adds. “Western Great Lakes does a really great job of honoring the child that has been lost and getting the milk to babies who need it. Or, if there is only a small amount of milk, it can be used for research. That’s a really cool thing they do.”

Donor mothers don’t receive financial compensation, Chay notes. “They do it out of the good of their heart for other mothers in the community.”