It used to be that heart surgery was invasive and uncomfortable, but thankfully those days are waning as new innovations revolutionize the way physicians treat common conditions.

Cardiology is constantly evolving.

That’s part of the attraction of the field, says Dr. Asim Zaidi, interventional cardiologist and medical director at Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Medicine McHenry and Huntley Hospitals.

“It’s not a stagnant field,” Zaidi adds. “There’s always something new coming out, something more advanced, that enables us to deliver more care to patients. Now, we can say different things to patients: ‘We can try this procedure – we can have you see this expert.’”

The constant changes in cardiology should provide some relief to patients, especially if they have unfavorable memories of past procedures.

“I think patients oftentimes have a fear of procedures because of an experience they had, or someone they know had, 15 years ago,” says Dr. Jeff Freihage, interventional cardiologist at Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital in Barrington. “But every 5 to 10 years, things improve, get safer, get more comfortable for patients. I think that’s important for patients to realize: The arena for cardiovascular patients is becoming quicker and less invasive, and the patient goes home sooner. Complication risks are a lot less, and there’s less discomfort.”

Updating Older Technology

There have been lots of “little” advancements in certain therapies, procedures and devices used in cardiac care that may not be well-known to patients who have older relatives who underwent procedures for similar conditions.

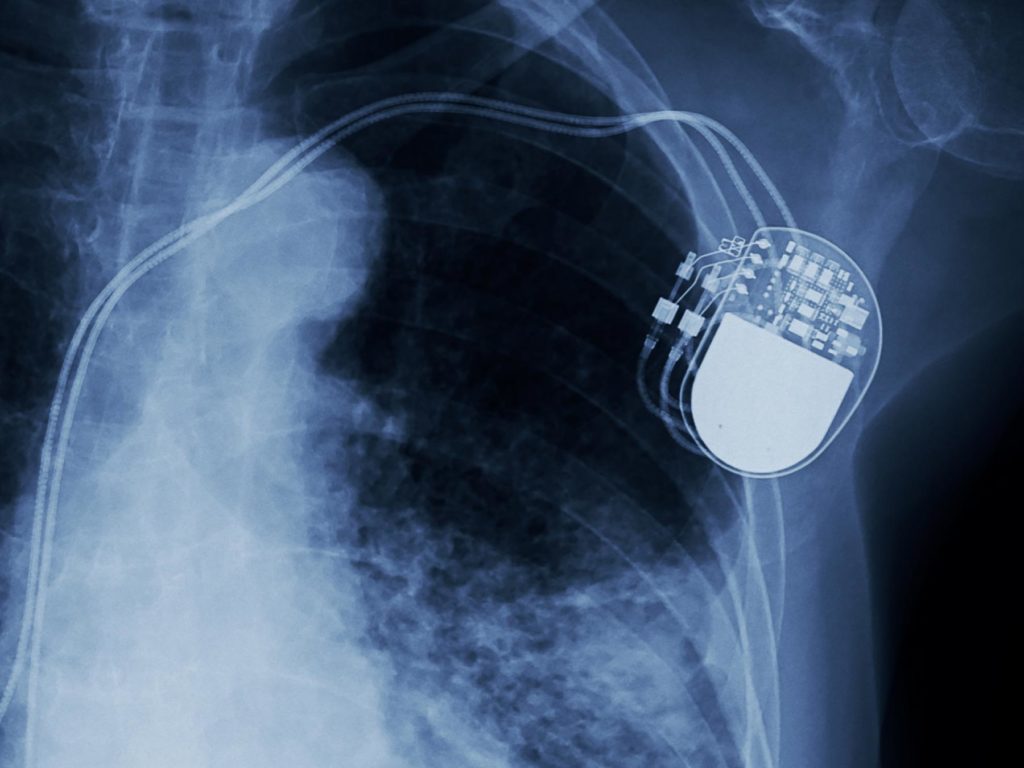

A traditional pacemaker, for example, is a small metal box that sits underneath the skin and has wires – or leads – that go into the heart and help treat some arrhythmia, which is an irregular heartbeat, Zaidi says. In 2016, however, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a leadless pacemaker called Micra.

“Leadless pacemakers sit in the chamber of the heart,” Zaidi says. “It’s like a small capsule or vitamin, it’s delivered through the vein, so no incision is needed, and it doesn’t require any wires. Not everyone’s a candidate for that, but those types of things are developing more. Though a pacemaker has been around for decades, there’s still evolution.”

Similarly, in 2015 the FDA approved the WATCHMAN device for those with atrial fibrillation, an irregular heartbeat, in the left atrial appendage (LAA). This is a pouch-like extension of the left atrium. Atrial fibrillation can increase the risk of blood clots that form in the heart, travel to the brain and cause a stroke, Zaidi says.

“The common method to reduce the risk of stroke is starting people on blood thinners like warfarin,” he says. “But people don’t like being on blood thinners. They can be inconvenient, they require regular blood tests, and some newer agents are expensive. Also, the downside to a blood thinner is the increased risk of bleeding. This is where WATCHMAN is currently an option.”

Essentially, the WATCHMAN device is a plug that sits in the LAA where blood clots can develop. Blocking the LAA helps lower the risk of stroke and bleeding.

In 2014, the FDA approved the CardioMEMS HF System to help physicians and their teams monitor heart failure patients’ symptoms from the patients’ own home.

“People with heart failure have a heart that is weak in pumping function, which can cause fluid buildup around the lungs and cause shortness of breath,” Zaidi says. “It’s a very common reason for people coming into hospital – they’ve developed too much fluid in their system. Heart failure exacerbations are a very difficult, challenging disease to treat.”

To help monitor heart failure patients, the CardioMEMS device has a little wire encased in a small plastic box that’s implanted through a vein into the pulmonary artery.

“It’s clever,” Zaidi says. “With a special pillow, people every evening would lie on this pillow that sends out a frequency to this wire that resonates and sends results back to our team with a number that’s a correlation with the amount of fluid in the person’s body. Our heart failure team monitors these results. If the fluid status is going up, then we intervene early and we call the patient. They may not even be feeling anything, but we’re keeping an eye on their readings every day while they’re at home.

“This is something we’re doing more and more of,” he adds, “because as soon as someone gets into hospital the data shows they get more complications. With heart failure patients, the key is to keep them out of hospital.”

Same-Day Discharge for TAVR Operation

In some ways, the transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is old news in cardiology.

Many area hospitals, including Ascension Alexian Brothers in Elk Grove Village and Ascension Saint Alexius in Hoffman Estates, can perform the procedure. It’s non-invasive way to replace one of the four heart valves through a catheter rather than open-heart surgery.

“Replacing the valve through the groin has become more and more common,” says Dr. Jack Chamberlin, Ascension Illinois Heart and Vascular Physician Lead and cardiologist at Ascension Alexian Brothers and Ascension Saint Alexius. “We did our 1,000th patient this last year. We have a very accomplished team – we do six to seven TAVR procedures a week – and the biggest thing is, we’ve been doing it for a while – eight or nine years. We’ve really done the high-end, difficult ones that can’t be done anywhere else.”

In early 2020, Dr. Andrei Pop, an interventional cardiologist and director of the structural heart disease program at Ascension Illinois, started focusing on how to better streamline TAVR to reduce time procedurally and post-op, which allowed qualified patients the potential to be discharged the same day.

“This all started during COVID when hospitals were struggling to have beds and do these procedures that would take up a unit bed,” Chamberlin says. “Today, if they’re stable at the end of the day and meet certain criteria, they can go home.”

The percentage of TAVR patients who qualify for same-day discharge has increased to 20-40%, Chamberlin says.

“That’s a huge thing,” Chamberlin says. “The first year we did this, it took a bit to catch on. The second year, it became a really big deal. It’s not routine, but our team is so good at this, and there are so many fewer people in the room, and it’s so slick. If you think about it, 1,000 patients is a lot of valves. We have highly experienced people here. That’s a comfort I also have.”

Mitral Valve and the MitraClip

The structural heart arena includes TAVR procedures as well as another common valve procedure.

The mitral valve lies between the two chambers on the left side of the heart: the left atrium and the left ventricle, says Freihage of Advocate Good Shepherd Hospital.

The left ventricle, or pumping chamber of the heart, pumps and opens up the aortic valve so blood can leave the heart.

“But at the same time, the mitral valve closes in order to prevent blood from going back into the left atrium,” Freihage says. “If you have significant blood going back to the left atrium, pressure in the lungs’ vasculature increases. People are short of breath, and they feel lousy.”

A floppy mitral valve is known as mitral valve prolapse, where the valve prolapses or sinks into the left atrium.

In many instances, surgery is superior to other methods of treating the mitral valve, says Freihage, but some patients may be able to use mitral valve therapies not available in the past.

“For young people, they can get a good surgeon for a good valve repair, and the patient is essentially cured for life of that problem,” Freihage says.

However, some patients have had mitral valve prolapse their entire life but have never needed surgery because the degree of leakiness of the valve didn’t warrant the procedure. These sorts of patients may find themselves becoming more symptomatic as they reach their late 70s or early 80s, Freihage says.

At this later stage in life, surgery isn’t always the best option.

“For those patients, there are now therapies such as the MitraClip, where you put a clip on the valve to tether it together so you don’t have the severe leakiness that you had previously,” Freihage says. “The patients feel better and live longer.”

A second set of people – those with congestive heart failure – also are candidates for a MitraClip.

“When the door frame of the valve has gotten bigger and the valve doesn’t completely close together, there are no surgical options,” Freihage says. “If they have a bad heart, a weak heart, and we try to fix the mitral valve by replacing it, they tend to not do very well. They do benefit from the MitraClip. We have an option that we previously didn’t have to allow patients to benefit from a mortality standpoint and also a morbidity standpoint of feeling better.”

Advocate Good Shepherd is working to have this procedure available in the near future, Freihage says.

Filling the Gap

While many area hospitals have fantastic heart failure teams to work with patients who experience all kinds of cardiovascular conditions, it may be worthwhile to see if your particular hospital has a heart failure support program or clinic to provide support after your procedure or hospital admission.

About four years ago, Ascension Illinois created an advanced heart failure clinic that had two components: advanced nursing support once a patient leaves the hospital, and a mechanical support program for patients with severe heart failure and for whom a heart transplant is not an option.

“We provide a lot of support after a heart procedure to prevent another admission – to help people make it at home,” Chamberlin says. “That was the gap in the past: we’d take care of them in the hospital. Now, our heart failure clinics have been fantastic to fill in the gaps. They do a wonderful job.”

Ascension Illinois completed its first left ventricular assist device (LVAD) procedure in 2019, which implants a battery-operated “mini artificial heart that can really help people who can’t get a heart transplant but need something else,” Chamberlin says.

The heart failure clinic began using advanced practice nurses and dietitians to provide more support to these patients.

“A lot of patients would say, ‘I don’t know what to eat,’” Chamberlin says. “They have examples of diets to follow, but they would say, ‘I don’t know how to measure a 1.8-gram sodium diet; what is that? How much is too much? How do I know how to take my blood pressure correctly?’”

In the clinic, nurses and dietitians provide practical advice on what to eat, Chamberlin says. They also give patients a scale that sends data back to the nurses because “it’s tricky to get people to weigh themselves every day,” he says.

Heart failure patients typically are seen at the clinic within 48 hours of hospital discharge to go over routine habits they’ll need to successfully monitor themselves at home, Chamberlin says. They come back in one or two weeks for a followup, which sometimes includes labs. Usually the frequency of visits slows down after that.

“Once you get three months down the road, the risk of recurrence is much less,” Chamberlin says. “Some people keep in touch every six months or year, just to see how they’re doing and make sure they’re staying on track.”

Find the Problems Early

Freihage believes it’s “fantastic” that interventional cardiology can provide therapies and procedures that are “less invasive for the convenience of the patient” while also causing less pain and less morbidity with the same long-term outcomes as surgeries in the past.

However, the first step of heart health is to keep in touch with a primary care physician, he says.

“You have to have a doctor, and you have to be doing your routine screening,” Freihage says. “A lot of times, valve or heart disease is picked up on during physical exams. A doctor orders an echocardiogram, and that triggers surveillance. Sometimes, the disease process is mild. Primary care physicians will know what the first steps are, and in a couple years they’ll do another echo.”

Other times, that routine physical exam could trigger a consult to a specialist, especially if the disease advances.

“It’s important to sit down with your physician once a year and talk about if you have any changes in your functional capacity, etc.,” Freihage says. “These valvular disease issues don’t appear out of the blue. They’ve been there for a while before they become symptomatic. It’s much better for a primary care physician to hear a murmur, so when it’s time to do a procedure on a valve they’ve been following you for two years. When they present when they’re severe, that means the health system has failed us. Ideally, we should be picking up on these when they’re mild or moderate.”

The ultimate goal of primary prevention is to get to the point where all disease processes are caught in the early stages so proper care can be given, Freihage says.

Even then, however, he doesn’t see the volumes of cardiology patients decreasing. But for good reason.

“Patients are living longer,” he says. “We are doing a better job of finding things and treating things. We’ve been routinely doing procedures on patients in their 80s without thinking about it being a risk factor for adverse effects. Now, it’s patients in their 90s and 100s that we may worry about because they may be a little more brittle. We’re more aggressively treating patients when they’re younger.”