It’s a fitting tribute to the patron saint of travelers and healers that a brand-new church in northern Lake County is assembled from a pair of forgotten parishes . That it all came together – and how it happened – is, in some ways, a miracle.

Five minutes south of the Wisconsin border, in the middle of a field right off U.S. Route 45 in Old Mill Creek, sits a mammoth limestone church.

If you go by the 2010 construction date on the top of its cornerstone, St. Raphael (pronounced RAY-fee-el) the Archangel Catholic Church is the youngest parish of the Chicago Archdiocese, which serves approximately 2.2 million Catholics in Lake and Cook counties.

But the bottom portion of the cornerstone – which bears a Latin inscription and the Roman numerals for 1918 – alludes to a unique architectural history that dates the church back more than a century.

“I think people are curious,” says parishioner Grace Bower Cockey, of Lake Bluff. “It’s a beautiful Chicago Catholic church in the middle of a cornfield. I think there are definitely a lot of architectural and historical elements that draw people in. Obviously, they stay for something else, though.”

St. Raphael’s, 40000 N. U.S. 45, named after the patron saint of travelers, is a giant puzzle of a building, pieced together with structural components and precious artifacts from churches the Chicago Archdiocese has closed over the past several decades.

Its limestone facade, including its 1918 cornerstone, was salvaged from St. John of God, a Polish parish in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood that celebrated its last Mass in 1992.

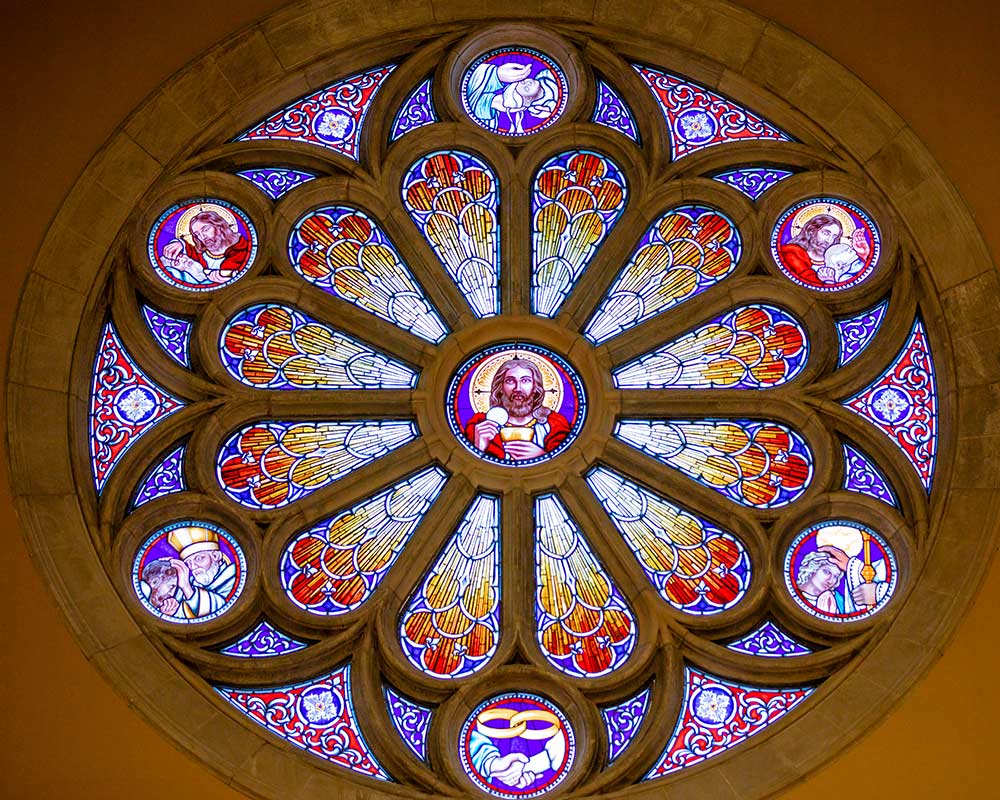

Much of St. Raphael’s inside – including the solid oak pews, marble statues and altars, and stained-glass windows – came from St. Peter Canisius, a parish built in the mid-1930s that served Chicago’s predominantly Italian Austin neighborhood before closing in 2007.

Drawers of vestments arrived from a closed Chicago seminary; chalices, vessels, cathedras (priest’s chairs), artwork, kneelers and other furniture came from additional closed parishes, says Father Matthew Kowalski, who has pastored St. Raphael since 2020.

The result is a stunning melting pot of new and old that captivates visitors and members alike – at a fraction of the cost of what would have been spent on a completely new construction.

The church property and the building as it currently stands cost roughly $10 million, says retired Fr. John Jamnicky, the first pastor of St. Raphael who helped build the church.

“The doorknobs are all carved brass; the 20 doors are 11 feet tall. Where do you get things like that?” he says. “That’s why I tried to use as much of the things that were not being used, that may have possibly been destroyed, and now we have something very special and very sacred and very old as a house of God.”

Planning Ahead

When the late Cardinal Francis George asked Jamnicky in July 2006 to start a new parish in Lake County, there had not been a new parish in the Chicago Archdiocese in 22 years, Jamnicky says. That was partly because there weren’t many rural areas left to develop in Lake and Cook counties.

At the time, the Antioch area was headed for major expansion, and the diocese was trying to plan ahead.

The Clublands of Antioch alone was supposed to add around 965 homes off Illinois Route 173 on the east side of the village.

But, as is common with many subdivisions of the time, things didn’t go according to plan. Only about one-third of the original Clublands houses were built before developer Neuman Homes went bankrupt in 2007.

“I went up there in July 2006; St. Raphael became a canonical parish in April 2007. And then the Great Recession hit by 2008,” Jamnicky recalls. “Before that, it was like boom town around there. That was the reality.”

Still, Jamnicky had faith.

“I figured this church will be ready when the population increases – and it will increase at some point, no doubt about it,” he says.

Today, St. Raphael has 600 families in its books. Attendance normally hovers around 400, spread throughout the church’s three weekend Masses, Kowalski says. St. Raphael’s five Christmas Masses saw 1,000 people in total.

“The church was built with the idea that this will be a big parish, but the economy is taking its time,” Kowalski says.

Starting from Scratch

Recession aside, there were still plenty of people who needed a Catholic church home in the mid-2000s in northern Lake County. But Jamnicky was starting from scratch. While rustling up artifacts for a new church, Jamnicky had to figure out where to hold services.

While driving around his new territory, which stretches from Antioch to Wadsworth and Grass Lake Road to the Wisconsin border, he noticed a farmhouse for rent near the corner of Ill. Rt. 173 and U.S. 45.

“I said, shoot, this is a great spot!” he says, laughing.

It was near a 40-acre parcel the diocese had purchased decades earlier, and it included a farmhouse – which Jamnicky figured he could utilize as his residence and the church office – plus barns and farm buildings that could be renovated into a temporary church and church hall.

“Lo and behold, as I contacted the real estate agent, here one of the most prominent and wealthiest Catholic families in the whole new parish area owned the farm and the house,” Jamnicky says. “It was the Pedersen family, who owned a GMC dealership, which closed down during the recession.”

Alfred and Florence Pedersen were unbelievably cooperative, Jamnicky says.

“Mr. Pedersen’s mother was a very devout Catholic,” Jamnicky says. “He said his mother would be so honored if there were to be a Catholic church there on their land. That’s what we wound up doing.”

From Barn to Church

Norma and Patrick Lucansky of Antioch were some of the first parishioners of St. Raphael.

Norma Lucansky, 84, remembers when St. Raphael celebrated its first Mass in the converted machine shed on the Pedersen farm.

“That was such a cute country church. We loved it,” she says. “We took Mr. Pedersen’s barn where he repaired all his equipment, and Father Jamnicky and business manager Richard Gambla salvaged whatever they could from local churches.”

The barn church quickly grew to 250 parishioners, and when Cardinal George blessed the church, he made sure to comment on its furnishings.

“The cardinal himself said, ‘This is by far the most beautiful temporary church I have ever seen,’” Jamnicky says. “It was a beautiful, wonderful little country church, and the people loved it, and the numbers just grew and increased. We were standing room only six months after we opened.”

Though the diocese owned 40 acres north of the Pedersen farm, Jamnicky wasn’t convinced it was the right spot to build a permanent facility. Its location 1.5 miles from the Wisconsin border meant the majority of the parish would have had quite the drive every Sunday.

He persuaded the Chicago Archdiocese to look at a 150-acre farm further south on Route 45 in Old Mill Creek, and thus it bought the Eberhardt property, with 23 acres allocated for the construction of a permanent church, and nearly 20 more acres set aside for a possible rectory and future expansion.

Once the location was established, Jamnicky went back to Cardinal George and reminded him of a conversation they had shared at the blessing of the temporary church.

“Cardinal George used to like to crack little jokes,” Jamnicky says. “And he said to me, ‘Boy, this is something else you’ve done! I oughta give you St. John of God church for up here.’ It was just a joke; he wasn’t serious. But I had already been thinking that exact same thing.”

Combining Histories

When St. Raphael parishioners first started fundraising for their new church home, they made a request.

“The people would say to me, ‘Father, please, please, build a church that looks like a church,’” Jamnicky says. “So, I always had that in mind. Even that temporary church had the most beautiful artifacts of our faith.”

Jamnicky was aware St. John of God was designed and built by architect Henry J. Schlacks, whom Jamnicky says “built some of the most beautiful churches in Chicago” around the turn of the century.

With Cardinal George’s permission, Jamnicky took an architect and structural engineer to examine St. John of God, and they found the Renaissance-style church was in poor shape after sitting vacant for nearly two decades.

“It wasn’t going to be too long before the roof was going to cave in,” Jamnicky says. “I went back to the cardinal and told him it was not practical to move the church. But the facade, the whole front of the church, was in such great shape and architecturally so well done, and the doors and the steeples and the narthex areas around the side were so fine. They estimated that it could be taken down and could be transported, stone by stone, up north to the present building site for approximately $2 million.”

So, St. Raphael had the shell of a building – complete with two 140-foot-tall steeples and three large bells – but the church had no interior.

Jamnicky heard of another Chicago church, St. Peter Canisius, that had been empty for about five years but was heated and protected the entire time.

“I went in there and, coincidentally, architecturally it was the same size as St. John of God,” Jamnicky says. “I asked permission to take the interior of St. Peter Canisius, and I got permission to do that.”

With most of the puzzle pieces in place, N. Batistich Architects oversaw the building of St. Raphael, and on June 27, 2010, the church hosted its groundbreaking service.

Four years and one day later, parishioners celebrated the first Mass in St. Raphael after more than 200 people completed a 2-mile procession down U.S. Route 45 carrying “incense and rosaries and prayers as we walked to bring Christ from the temporary church to the new church,” Jamnicky says.

Some portions of St. Raphael have been replicated, like the 25-foot rose window at the front of the church, merely because the original from St. John of God was unsalvageable. The painted arched ceiling, which stands 60 feet tall, also was re-created to imitate what was in St. John of God.

If you know where to look, you’ll find other treasures tucked inside. All but three of the 18 stained-glass windows are original, imported from Innsbruck, Austria, to St. Peter Canisius before making their way to St. Raphael. The main altar and two side altars reclaimed from St. Peter Canisius were commissioned by an Italian firm in Italy.

“They completed the altars, but then World War II broke out,” Lucansky says. “They hid them in caves, and the German army never found them. Eventually, they shipped them to St. Peter Canisius. The small altar in front, where Father says Mass, was made to match those.”

Future Construction

Despite St. Raphael’s size and grandeur, it isn’t as large as Jamnicky had intended.

“The diocese wouldn’t let me build it as big as I wanted to build it,” Jamnicky laughs. “I wanted a church with about 1,500 capacity. They pulled me down to 700; then I snuck in with architects to accommodate 900.”

Still, Jamnicky made sure St. Raphael was architecturally sound. It’s built to withstand an earthquake, and it’s designed for expansion. But parts of the vision are still on paper only.

St. John of God stood at 140 feet tall with its two bell towers, and Jamnicky desperately wanted to have them erected at St. Raphael before he retired in June 2016 at the age of 71.

He even salvaged three additional bells from St. Simeon’s, a Bellwood parish west of Chicago’s Loop whose bell tower was scheduled to be demolished.

The century-old cut limestone pieces still sit – labeled and ready – in a field next to the church, while the bells sit in storage. It will cost at least $750,000 to re-erect each steeple, Kowalski says.

Similarly, a rare 1915 Austin pipe organ from Chicago’s Medinah Temple also sits in a storage barn, waiting to be resurrected. It will cost at least $500,000 to rebuild the pipe organ, Kowalski says.

Those are large, expensive projects that the church will have to save for, as is the building of a small rectory on the property, says Kowalski, who currently lives off-site.

Kowalski says he soon hopes to complete smaller, less-expensive projects, including landscaping and planting trees around the parking lot this summer.

The new church office space should be ready soon, allowing Kowalski and his five part-time staff members to move from a farmhouse just south of the church into the church’s basement.

Within the next six months, the rest of the church basement also should be finished, providing parishioners a larger fellowship area to gather after Mass.

“We were able to start using it, but I used to always tell people that the great churches of the world took 100 years or 200 years to build,” says Jamnicky, who came back to visit St. Raphael to celebrate 50 years of ordination in 2022. “So, to finish St. Raphael, it may take some years.”

Though St. Raphael makes a statement, some may question the time and effort it’s taken to repurpose old churches, rather than simply building new.

For one thing, parishioners wanted a classical-looking church, and it’s an expensive proposition, says Jamnicky. But there’s also a sentimental aspect to resurrecting stone, wood and glass that have witnessed generations of believers.

Shortly after the outer walls of St. Raphael were complete, a young woman asked Jamnicky if she could get married in the church.

“‘My great-grandmother, my grandmother and my mother were all married in St. John of God’s church, and I would like to be married in St. John of God,’ she told me,” says Jamnicky, recalling his promise to help. “That’s how much these old churches meant to people.”

The Future of St. Raphael

Grace Bower Cockey and Brennan Cockey of Lake Bluff joined St. Raphael in 2019 when Fr. Michael McGovern (now Bishop) was pastor. They were married there in 2021 and have seen how much the church has grown in the past few years.

Brennan is a music teacher at Washington Elementary School in Waukegan who sings in the choir and is a substitute cantor. The choir now averages about 10 to 12 people, he says. But even six months ago, there weren’t that many choir members, adds his wife, Grace, who heads the social committee for the church’s women’s group.

“New members are starting to come in,” she says. “It’s a very exciting time for St. Raphael because we’re finally getting warmed up again after the frost of COVID-19. I think that’s why we’re starting to see more young families again.”

Kowalski says there has been a “steady trickle of young families with kids” who have joined the parish, and last year, 30 babies were baptized – a record for St. Raphael.

“I think we have a really intricate history with St. Raphael being combined from different churches in Chicago,” Grace Bower Cockey says. “But I think we’re going to have an even more amazing future. We’re a growing parish; we have a lot to look forward to.

“And the church expands past any building,” she adds. “It’s where we come together as Christians, worship God, and act in service to others – whether that’s in a barn or a church.”