Imagine the government is telling you an epidemic outside your door is “only the flu” and not really serious. But you hear rumors that people are dying like flies. You’re asked to take in a few new orphans or to host out-of-town mourners or, God forbid, to nurse the sick. You’re terrified of exposing your own household to sickness. But your help is needed. Would you roll up your sleeves to help? Or lock the door and hide? People in our region and across the globe faced that ghastly choice 100 years ago during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918.

One century ago our ancestors experienced a tragedy so enormous that we’ve never fully reckoned with it. We’ve treated the 1918 flu pandemic like an embarrassing relative no one wants to talk about.

And yet, “It was a plague so deadly that if a similar virus were to strike today, it would kill more people in a single year than heart disease, cancers, strokes, chronic pulmonary disease, AIDS and Alzheimer’s disease combined,” writes Gina Kolata in her book, “Flu.” She marvels that, as a microbiology major and history class student, the subject of the 1918 flu never came up during her college years.

The virus sickened about 500 million people and killed 50 to 100 million, or 5 percent of the global population. This included at least 670,000 U.S. citizens. That’s more Americans than were killed in battle in World War I, World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War combined, notes Kolata.

The world’s worst pandemic exploded at the end of World War I. The war had already weakened human health via hunger, stress, poor sanitation and exposure to extreme cold. The Great War didn’t cause this freakishly virulent strain of influenza to develop, but it certainly hastened its spread, as more people moved around the globe than ever before, living and breathing in crowded ships, trains, barracks, tents, trenches and hospitals.

The war also bred chaos and censorship. The true number of flu dead is impossible to pinpoint because countries like populous India, which was especially hard hit, kept no records. Other countries, including ours, downplayed losses to fool enemies.

In the U.S., about 20 percent of those who got the 1918 flu died, compared to 1 percent in more typical flu epidemics. This is only an average. In some cases, entire communities were wiped out, especially among Eskimos and Native Americans.

Rockford was hit especially hard because of nearby Camp Grant, one of 16 U.S. National Army training camps built in 1917 to produce soldiers as quickly as possible.

It’s estimated the flu killed at least 2,300 people at Camp Grant and several hundreds more throughout Winnebago County, within five weeks. (That’s about the same number of souls who perished at the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001.) Victims died so quickly that recordkeeping became a blur.

Along with chaos, censorship further confused the story of the Spanish flu. Although it seems unthinkable today, publishing or speaking negative news in the U.S. earned violators a 20-year prison sentence, under the Sedition Act of 1918.

“That era was a real stain on our country,” says Terry Dyer, a local historian and author. “It certainly wasn’t an environment that encouraged truthful reporting.”

Even the pandemic’s misleading nickname is owed to censorship.

“The flu didn’t start in Spain and wasn’t any worse in Spain,” explains Bruce Olson, who gives local presentations about the Spanish flu. “But Spain wasn’t part of the war in 1918 – it was a neutral country – so its press freely reported the horror of the pandemic.” Spanish King Alphonso XIII was sickened by the flu, but so were other world leaders who concealed it from the press.

Some scholars, including Dyer, believe U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was secretly weakened by the flu while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles. They say it’s why he didn’t hold his ground against French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, whose demands for overly harsh treatment of Germany set the stage for World War II just 21 years later.

“Clemenceau insisted that Germany take full responsibility for the start of the war, which was nonsense,” notes Dyer. “Austria and Serbia started the war after a Serbian nationalist assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, in Sarajevo. Germany was a powerhouse ally of Austria, but it didn’t start the Great War.”

It’s ironic that, just as the Great War set into motion every U.S. war since 1918, the H1N1-A Spanish flu set into motion every flu pandemic since 1918. See related story, “Could It Happen Again?” (at bottom).

So where did this freakish flu strain originate, if not Spain? That remains a mystery, as do several of its anomalies. Why did it hit hardest in fall, not winter like most flu? Why did it hit healthy young adults age 20 to 40 the hardest, in a W-curve rather than the usual U-curve that mostly kills the very young and old? And why did it kill so quickly, sometimes within hours of first symptoms?

“We’re still not certain why this strain was so much more deadly,” says Dr. Gary D. Rifkin, professor emeritus and chair of the Department of Medicine and Medical Specialties at the University of Illinois College of Medicine-Rockford. “One theory is that it acquired a certain chemical from a bird flu on its surface proteins. But it’s not at all clear why young people were so hard hit. As for where it originated, there’s no definitive data.”

But there are theories.

One points to pig farms in Belgium. Another to Kansas. Science writer John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza,” believes a blend of human and bird viruses infected the same pig cell in a pig raised in Haskell County, Kan. It moved with men to Fort Funston, in central Kansas, a training camp similar to Camp Grant. The first odd flu case was documented there March 4, 1918.

“Within two weeks, 1,100 soldiers were admitted to the hospital, with thousands more sick in barracks,” Barry writes. He thinks they carried the flu to other U.S. camps and to Europe, from which it spread in every direction, evolving along the way.

That spring 1918 wave of Spanish flu was the first of three waves and was relatively mild, although it killed people, as nearly all flu outbreaks before and since have done. (The 2017 flu season killed 80,000 Americans, up from the average 41,000. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reports that 80 percent of the children who died were not vaccinated).

“Sometime between spring and late summer 1918, the virus mutated into a much deadlier flu,” Rifkin explains. “Influenza normally inflames only the lining of the throat and upper bronchial system. This flu also inflamed the lungs, making patients susceptible to bacterial and/or viral pneumonia on top of flu. This secondary infection is what killed them. As their lungs rapidly deteriorated, they could not get enough oxygen and died.”

Antibiotics for fighting bacterial infections didn’t come into use until the 1940s; patients were treated with aspirin and quinine. People often spread flu before they knew they were sick. Symptoms hit suddenly, including high fever, head/body aches and a severe cough that produced blood-streaked pus. Blood might ooze from a patient’s nose, mouth, eyes or ears. A lack of oxygen caused cyanosis – a bluish darkening of the skin – and high fever caused delirium.

This second, deadliest wave of Spanish flu arrived on the U.S. Atlantic seaboard in late August and raced westward. A third, milder wave returned in spring 1919.

Camp Grant & Rockford

Rockford was a prosperous city even before World War I weapon production caused wages to triple in 1917. But it really “hit the jackpot” when construction began on Camp Grant that year.

“It was the single largest construction project Rockford has seen before or since [in terms of scope and size], employing 8,600 workmen,” says Dyer. “People today don’t comprehend how enormous Camp Grant was. It sprawled across 6,000 acres.” To visualize this, picture 4,600 football fields with end zones.

The camp was built for 48,000 people and at one point housed 57,000. Rockford’s population was about 60,000. “So you basically had two self-contained cities within 5 miles of each other, sharing a lot of social interaction,” says Dyer.

Rockford landmarks like the Midway Theater and the Inglaterra Dance Hall (later the ING roller skating palace) were built by camp contractors and dedicated in 1917 to Rockford citizens “and their guests, especially the men of Camp Grant.”

Early in 1918, the camp housed about 30,000 men, mostly from the Midwest, plus hundreds of nurses in training. It was deemed exemplary in its health standards after a June inspection.

But by September, the camp population had swelled to more than 40,000. A new camp commander arrived in September, Col. Charles B. Hagadorn, age 51, a West Point graduate who had fought with distinction and was “married” to the military. Perhaps because the previous winter had been notoriously cold, Hagadorn worried about the men housed in tents.

Against the advice of senior medical advisors, and violating Army health rules, he ordered, “There must be, by military necessity, a crowding of the troops.”

It was a decision he would deeply regret.

Men from tents crowded into already-full barracks even though Hagadorn knew flu was sweeping through other camps.

“But Hagadorn believed that disease could be controlled,” writes Barry. “After all, this was ‘only’ influenza.”

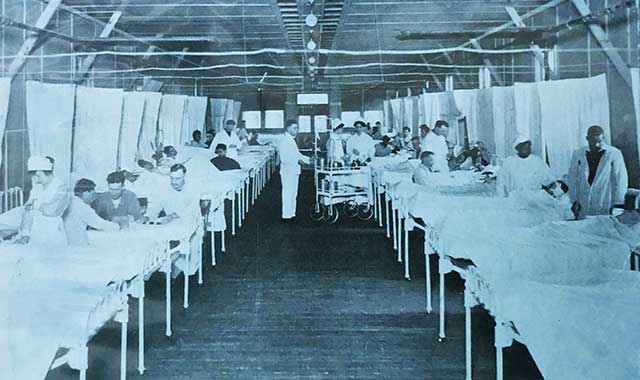

The very next day after issuing that Sept. 20 order, flu patients began trickling into the camp hospital. By midnight, 108 men were sick. Within two days, 400 soldiers were in the infirmary. Within a week, that number grew to 4,000 and the following week peaked at 10,713.

The camp hospital was wholly unprepared for sickness on this scale. There were shortages of everything – aspirin, sheets, thermometers, cots. Mules grew too exhausted to haul ambulance carts of sick men to the 61 makeshift infirmaries made by relocating healthy men to tents. Sick men spilled onto barracks verandas, which workmen scrambled to cover with roofing paper before a major autumn storm let loose.

“The stretched-thin medical staff began to collapse from exhaustion and sickness,” says Dyer. “The camp dropped its prohibition of black nurses and brought them in to tend black soldiers. White nurses weren’t allowed to tend black soldiers. But the black nurses had to wait for segregated housing to be built before they could come.”

Nearly 400 nurses couldn’t keep up with the filth-soaked beds of patients who were often delirious with fever. The camp attracted thousands of flies.

The same scene played out in training bases nationwide as some 30,000 trainees fell ill. On Oct. 25, the State of Illinois announced that 1 million residents had become sick in the past month. All war training stopped. Healthy men unloaded supplies from trains, prepared food and hauled corpses. Barry reports that 250 Camp Grant men did nothing but stuff sacks with straw to make a steady supply of new mattresses.

Adding to the confusion was a growing stream of out-of-town visitors, some of whom tried to bribe hospital workers into providing extra care to their sick loved ones. This forced Chief Medical Officer Lt. Col. H.C. Michie to issue a stern warning against accepting bribes.

The Red Cross constructed a tent waiting room area on the base for these distraught visitors, but out-of-towners had no place to sleep since Rockford hotels were full. Many found warm beds and hot meals in the homes of generous local families.

Courageous Volunteers

Residents of Winnebago County were especially hard hit by this flu because of contact with Camp Grant. By the end of the first week of outbreak in Rockford, City Health Inspector W.H. Cunningham, M.D., reported that as many as 2,000 Rockford residents were sick. This number is likely under-reported, since many rode out their illness at home.

From his own sick bed, Rockford Mayor Robert Rew declared on Oct. 4: “Owing to the prevalence of influenza and pneumonia in Rockford and Camp Grant, all schools, churches, clubs, theatres, dance halls and all places of public gathering will be closed until further notice.”

Local historians note it was the only time in Rockford history when churches were empty on Sunday mornings. Even funerals were prohibited.

In some U.S. cities, volunteerism during the flu crisis was suppressed by rabid fear and distrust fueled by propaganda.

For example, as Camp Grant death tolls climbed, the Chicago Tribune inexplicably printed “Epidemic Broken!” The government propaganda was meant to raise public morale, but often had the opposite effect.

“People could believe nothing they were being told, so they feared everything, particularly the unknown,” Barry writes. “With the truth buried, morale collapsed. Society itself began to disintegrate … in 1918, without leadership, without the truth, trust evaporated. And people looked only after themselves.”

This wasn’t entirely true in Rockford, however, where hundreds of volunteers of all ages, male and female, answered cries for help. Civilian doctors, nurses and many others risked their lives in service to the sick at Camp Grant.

“Under the guidance of a few professional nurses, 75 civilian volunteers kept temperature charts, administered medication and scrubbed floors,” says Dyer. “Some volunteers fell sick and died, including doctors and nurses.”

“They were absolute heroes,” says Olson.

A memorial arch dedicated to these heroic volunteers was erected at the camp in 1918 but was since destroyed.

Rockford families hosted visitors; students stayed after school and grandmothers burned midnight oil to sew thousands of gauze masks and gowns; and many civic organizations put their talent and good will to full use. Among them were the YMCA, the American Library Association, Knights of Columbus, the Jewish Welfare Board, Salvation Army, churches and various war service organizations. Red Cross staff worked tirelessly.

“At the War Camp Community Services (WCCS) headquarters, 111 S. Main St., visitors found automobiles operated by young women of the Red Cross motor corps ready to take them to Camp Grant. More than 1,000 people provided hospitality in their Rockford homes through the WCCS,” says Dyer.

Rockford hospitals overflowed; the third and newest, SwedishAmerican, had opened two months earlier, with 55 beds.

Along with volunteers, many Rockford buildings were put into service. The Knights of Columbus, Boys Club and Lincoln School buildings, as well Rockford Women’s Club, 323 Park Ave., were used as infirmaries. Women’s Club members had worked 22 years to fund and construct their shiny new Neoclassical building but generously welcomed the sick as first guests.

Too Many Bodies

Soldiers in training died at the rate of 75 to 100 per day, overwhelming the camp’s contracted undertakers, Murphy and Fitzgerald.

“Five other undertaking firms were appealed to, but there still wasn’t room in their morgues for all the bodies delivered from camp,” says Dyer.

Rockford businessman I.L. Bell, owner of the Overland Co. at 202-212 N. Church St., stepped up by allowing the company garage to be used as a Camp Grant morgue. The Western Undertaking Co. of Chicago sent several undertakers and five more came from Aurora, Ill. But it still wasn’t enough.

When Camp Grant Commander Col. Hagadorn summoned additional civilian undertakers to the camp, Bruce Olson’s paternal grandfather, Fred C. Olson Sr., was among them.

“My grandfather said that when he made that first visit to Camp Grant on Oct. 7, Col. Hagadorn was among the most distraught people he’d ever met. That’s really saying something. As funeral directors, we see a lot of distraught people,” says Olson.

Camp medical staff members told Olson Sr. they wanted to show him something terrible.

“They led him to a cordoned-off canvas military tent in which hundreds of dead bodies were stacked like cord wood,” says Olson. “The camp had no idea how to handle that volume of death.”

In an odd coincidence, Bruce Olson’s maternal grandfather also worked to embalm the dead of Camp Grant and Rockford. He was training at Camp Grant to be a medic when the pandemic struck.

“They thought medics-in-training knew more about the human body than most people, so they had undertakers teach them how to disinfect, embalm and prepare corpses to be sent by train back to their families,” explains Olson.

“There was an open field on Seventh Street, near First Avenue, where a canvas tent was erected and bodies were stored. My grandfather told me the instructing undertaker would stand on a riser and show about 30 or 40 medics, each assigned a corpse, what to do, step by step, almost like they were in a teaching lab. They handled about 30 to 40 corpses per hour.”

The dead weren’t just coming from Camp Grant, either.

“South Rockford families were particularly hard hit,” says Olson. “My grandparents described death wagons that rolled through the streets collecting the dead door-to-door. In some cases, two people would be sick and one would die. The survivor had no one to care for him or her and might die of thirst or starvation, too weak to get out of bed.”

Sometimes parents died, leaving small children behind. Many pregnant women died, including Olson’s paternal grandmother.

“My grandfather, Fred C. Olson Sr., survived the flu, although the high fever caused him to lose all his hair at age 30. But after his pregnant wife died, he was left alone to raise his small son, my father, Fred C. Olson Jr.”

High fevers caused by the 1918 flu sometimes caused permanent damage. “My grandfather’s sister was brain damaged from the fever and killed herself by jumping into the Rock River,” says Olson.

Deadly Remorse

Olson’s grandfather was correct to assess Col. Hagadorn as an extremely distraught man on that Oct. 7 day in 1918.

Early the next morning, after receiving the latest casualty list, Hagadorn ordered his sergeant to take everyone out of the headquarters building to stand at attention for inspection. The sergeant thought it odd, but complied.

Thirty minutes later the sergeant heard Col. Hagadorn’s Colt .44 pistol fire. The commander had taken his own life.

A surprisingly candid AP wire report heralded his death by suicide in newspapers coast to coast. It stated, in part, “Officers of the camp said he had been showing the strain imposed on him by the pneumonia epidemic, which has caused more than 500 deaths in camp. He had been troubled by insomnia.”

Within days of this event, flu casualties at Camp Grant declined. By the third week of October, they numbered only a few per day, although 800 sick men remained in the infirmary.

On Oct. 30, the ban on public gatherings was lifted. Camp Grant soldiers attended Rockford theaters and dance halls again for the first time in six miserable weeks. And less than two weeks later, millions of people worldwide poured into streets to celebrate the signing of the Armistice at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. Today we call it Veterans’ Day.

While 20th century historians credit military heroes with winning The Great War, more recent scholars suggest the virus played a far bigger role than has been acknowledged.

“A flu virus isn’t a very sexy way to end a war,” says Olson. “People would rather believe that their gorgeous general riding on his gorgeous white horse saved the day. But when you study the facts, you have to believe the flu had a lot to do with the way things played out.”

The 1918 flu brought every army to its knees, but it struck German soldiers at an especially critical moment, says Olson.

Traumatized

Nearly everyone who survived the dreadful 1918 influenza is dead. But even when they lived, they often were reluctant to talk about this terrible nightmare, conflating it with the war they desperately wanted to put behind them.

“The few times my maternal grandmother spoke of it, she spit out the word ‘flu’ as if it were a curse word,” recalls Olson. “You could just hear the anger in her voice. There was something like Post Traumatic Stress Disorder that affected Spanish flu survivors. People tried not to think about it.”

Olson began researching this pandemic about nine years ago because of its role in his family history.

“I think of the children who were never born into my family because the flu took out my grandmother,” he says. “How many, many families are there like mine?

“When I started to understand how huge an impact the Spanish flu had, not only on my family, but on the whole world and the way history played out, I really had to wonder, ‘What’s going on? Why do we know so little about this?’”

He adds, “The more you learn about it, the more you wonder, ask and realize.”

So, Could It Happen Again? …

The influenza of 1918 killed 5 percent of the global population, yet most of us dismiss flu as a nuisance, not a threat. Many people in 1918 also failed to take it seriously, confusing it with the common cold or a stomach virus, just as we do today.

“You can differentiate flu symptoms from a cold by the speed with which the symptoms come on,” says Dr. Gary D. Rifkin, professor emeritus and chair of the Department of Medicine and Medical Specialties at the University of Illinois College of Medicine-Rockford. “Colds generally take a day or two to come on. The flu hits you more suddenly with chills, muscle aches, headache and a fever that can get pretty high.”

The flu can’t be fought with antibiotics because it’s viral, not bacterial. But there are anti-viral medications that can be effective if taken within the first two days.

“Even if you’re not sure if you have the flu, seek treatment early,” advises Rifkin. “And don’t stockpile anti-viral meds in your medicine cabinet. That won’t work.”

Although doctors insist the best flu defense is vaccination, only 37 percent of adults over age 18 got flu shots last winter, down more than 6 percent from the previous year. Last year’s flu season turned out to be especially severe, with nearly double the average annual U.S. deaths of 41,000.

One reason people don’t get vaccinated is the mistaken idea that a shot will give them the flu.

“That just doesn’t happen because the virus in the vaccine is dead,” Rifkin explains. “Soreness at the injection site and low-grade fever are possible, but not the flu.”

People also question whether it will do any good.

“Most years, the flu vaccine is at least 50 percent effective,” says Rifkin. “And even if you still get the flu, it will likely be much milder, which is important.”

To be sure, the constantly evolving nature of influenza virus makes it a tricky beast for health officials to manage. Unlike chicken pox or measles, there’s no “one and done” flu vaccine for life.

“Influenza virus is not very well conserved, so it mutates,” Rifkin explains. “Each February, a committee decides which antigens will be used in that year’s vaccine. The virus may evolve during the time gap between February and the next flu season, so the vaccine may or may not be exactly what is needed.”

Flu season lasts about two months, usually starting in January. Vaccinations ideally should be completed in October because they take a few weeks to fully kick in, but getting them in December is still beneficial. Children under age 8 need two doses, ideally in early October and four weeks later.

There’s always ample vaccine. Rifkin explains that the most common way to produce flu vaccine is to inject selected viruses into fertilized hen’s eggs. After several days of incubation, the liquid is harvested and the live virus is killed. “This involves a LOT of eggs and it’s not speedy,” says Rifkin.

Two new vaccine production technologies are emerging – cell-based and recombinant. “But we’re not there yet,” says Rifkin. “The ability to manufacture vaccines much faster, using cell cultures instead of eggs, will be a huge milestone.”

There are four main types of flu virus, named A, B, C and D. Human A and B flus cause the seasonal epidemics. Type C causes mild respiratory illness and D mostly impacts cattle.

The A and B viruses are divided into subtypes based on surface proteins H (18 types) and N (11 types). The 1918 flu was H1N1-A. The recent bird flu in China is H7N9-A and so forth.

“Antigens” are molecules in virus surface proteins that trigger our immune systems to fight back by making antibodies.

“Drift” refers to gradual changes in flu virus genes that happen as the virus replicates. Over time, these collectively add up to something our bodies no longer recognize. That’s why flu vaccine is constantly updated.

“Antigenic shift,” however, is a sudden, major change in an A-virus that occurs when two animal viruses infect the same cell, as happened in 1918, explains Rifkin. “When the proteins from two completely different viruses infect the same cell, their proteins can mix together and produce something new and unexpected.”

“All influenza A pandemics since 1918 have been caused by descendants of the 1918 virus,” report flu researchers Jeffrey K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, who helped to unlock the Spanish flu gene sequence in 2005. They used 1918 virus samples recovered from a frozen Spanish flu victim in Alaska and the preserved tissue samples taken by doctors treating soldiers in 1918.

So, could a flu virus as virulent as the Spanish flu happen again?

“The likelihood is that we will have another pandemic,” says Rifkin. “We’ll go through an antigen shift that none of us has had in our bodies before.”

Because people now travel across the globe in a matter of hours, it will spread very fast. Vaccines won’t be developed rapidly enough to stop it. That’s the bad news.

“The good news is that, at least in this country, we’ll be better able to handle this antigen shift than they were in 1918,” says Rifkin. “We have better nutrition, better sanitation, less-crowded conditions. And we have anti-viral medications and antibiotics to treat bacterial secondary infections like pneumonia. The CDC is very involved with evaluation of the flu across the country and the Winnebago County Health Department is one of the best in the state, if not the country. We’re very fortunate.”