Before Wisconsin became the cheese capital, dairy farms in Kane and McHenry counties were milking a golden opportunity in Chicago. Join Jim Killam for a look into the industry’s past and the effort to protect the family farms and open pastures that still remain.

Beneath our region’s many subdivisions lies a story. And under that lies an even older one. Both are re-emerging thanks to local historians.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Kane and McHenry counties truly were America’s dairyland. The amount of milk, butter and cheese sold from Elgin in 1892 equates to more than $300 million in today’s dollars, says filmmaker Phil Broxham. And that’s not including peripheral producers of silos, butter tubs, milk cans and processing equipment. All told, the equivalent of a half-billion dollars drove the local economy – and stayed local, because the industry was all here.

Today, Kane County is a far cry from the country’s dairy capital, and what few farms do remain are disappearing rapidly. To preserve their story before it’s too late, the Elgin History Museum is teaming with Broxham’s Grindstone Productions to produce “Dairies to Prairies,” a documentary film and companion traveling exhibit.

“It’s a story that a lot of people don’t know all that much about,” Broxham says.

Prior to the mid-19th century, there really wasn’t a dairy industry. Even in cities, families owned cows and they would occasionally sell or barter unrefrigerated milk to neighbors. Then came Gail Borden Jr., a New Yorker who invented sweetened condensed milk in 1853. Vacuum sealing the milk into 10-ounce cans, he earned a federal contract to supply the product to the Union Army during the Civil War. Borden needed more factories, and Chicago offered rail connections to anywhere in the settled U.S. He bought a dairy in Highland Park but soon moved to Elgin because there were more dairy farms in Kane and McHenry counties. (It also didn’t hurt that Borden’s third wife, Emeline Church, came from Elgin.)

In the late 1860s and 1870s, the Borden plant required 10,000 gallons of milk a day to produce its Eagle Brand condensed milk, Broxham says. Six thousand cows from 107 nearby dairy farms supplied it.

While Borden put Elgin’s dairy production on the map, butter and cheese gave it its reputation, as hundreds of creameries sprang up among the farms. Eventually the new Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, with a station in Elgin, presented even greater opportunity. Milk could be put in glass-lined cans, cooled in streams, then sent by rail to Chicago.

“When one farmer started shipping milk to a hotel in Chicago and had a contract, the idea kind of took off,” says local historian Jerry Turnquist, a museum board member and the film’s co-producer. “People got on board. More and more milk was shipped from here, and more and more farmers converted to dairy farming around here.”

Trouble was, Chicago middle men were making more money than the dairy farmers. Some were cutting Elgin milk with either water or “swill milk,” from cows who had been fed mash from breweries and distilleries. Fearing for their reputation as well as their financial futures, Elgin producers in 1870 established their own board of trade, where sale contracts would be made and prices set. The board would soon establish dairy prices for most of the country for the next 40 years and be mentioned in the same breath as New York and Chicago markets.

Between 1880 and 1900, cows nearly disappeared from Chicago and almost all of the city’s milk arrived daily by rail. The market was so good for Elgin-area producers that they shifted nearly all production to milk instead of butter and cheese.

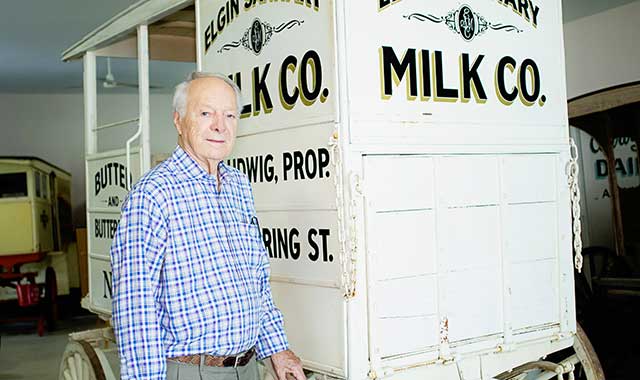

Refrigerated milk trucks came along in the late 1920s, and it became the predominant means of shipping to Chicago. By mid-century, regional dairies such as Ludwig, Bowman and Dean had become the major suppliers to the Chicago area. They sold to grocers, rather than consumers, eliminating the familiar milk men with their delivery wagons. Events like Harvard Milk Days, which has been celebrated for 77 years, still pay tribute to the region’s standing as a dairy capital.

A Bond with the Past

Just past a subdivision off South Union Road, in McHenry County, you’ll find the Bauman family dairy operation looking much like it did 50 years ago.

Where some of the area’s dairy farms have gone to robotic milking machines and operations more akin to Silicon Valley, the Baumans prefer to keep things simple.

“We’re not what a typical dairy farm looks like now,” says Renee Bauman, who’s 21 and wants to stay in the family business as long as she can. “We’re more like the old style. We don’t want to be bigger.”

Renee’s been helping in the dairy barn since she was 9, and she’s been milking cows since she was 13. After high school she received dairy certification from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Farm and Industry program. While she works mostly with the animals (and names every new calf), brother Randy, 18, prefers working with crops and machinery. He’s studying diesel technology at Kishwaukee College in Malta.

Renee and Randy are the fifth generation of Baumans to milk cows in this barn. Hermann Bauman, their great-great-grandfather, emigrated from Germany in the late 19th century and settled in Union with his wife, Marie. In 1895 they bought the 100-acre homestead; eight of their nine children were born in the farmhouse. They built the dairy barn in 1910, using local stones and lumber shipped from New England.

Hermann’s son, Erhardt, and his wife, Florence, took over the farm in the 1930s. By the 1950s Erhardt’s son, Ron, and his wife, Joyce, had begun dairy farming in nearby Huntley. When they retired, the dairy barn sat empty until Ron moved his herd back to the family homestead in 1984. Ron and Joyce semi-retired in 2008, and their son Ken, wife Beth and the kids moved into the adjacent house to take over the operation.

A decade later, Ron still helps Ken and the grandkids with milking and chores. They meet in the barn by 5 a.m. and milk 55 cows between 5:30 and 7 a.m. Two people run three milking machines each, with each cow requiring 3 to 5 minutes. Chores follow: cleaning barns and feeding not just the milk cows, but also the calves and heifers (females that haven’t yet had a calf). All told, the Baumans own more than 100 bovines.

By 10 a.m., the refrigeration truck from Dean Foods arrives, ready to transport the day’s milk to Dean’s Rockford plant for pasteurizing and processing. The Baumans have shipped milk to Dean since the company was founded in the 1920s.

The rest of the day is filled with field work, maintenance, tending to animals’ needs and running the business. Every evening, the morning’s process reverses – chores first, then milking, so the cows stay on a 12- to 13-hour schedule. The day’s work is generally done about 7:30 p.m.

None in the family are averse to hard work. But they also do the math.

“When I sat down to look at March,” Ken says, “and figured all the expenses for the dairy and the income, before I did any payroll, we had $94 – after we paid the feed bill, the electric bill, milk hauling, veterinary and everybody else.”

In addition to milking, the Baumans raise grain on 255 acres and custom harvest around Belvidere. They also market their bull calves. But for dairy farmers in this area, the handwriting is on the barn. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2017 agricultural census counted 3,000 cows in a county that once boasted almost 30 times that number.

The Baumans aren’t against technology or modernizing. They’ve looked at automation, explored producing organic milk and dreamed of building their own processing plant. For an operation of their size, there just isn’t enough financial incentive – or a clear enough view of the future – to take those risks.

“I think for us, in the back of our minds, it’s always, ‘How long are we going to do it?’” Ken says. “We’re getting by. We’re running neck-and-neck, production-wise, with the people with the technology. Right now, I’ve got cows eating grass in the pasture. I figure, let them do my work.”

For Renee, it’s about looking those cows in the eye each morning and evening. If one walks into the wrong milking stall (not common), Renee calls her by name and coaxes her to the right spot.

“Not everybody can get up and know that when they get to work, they’re going to be wanted,” she says. “They need us every single day, which is rewarding enough, if you ask me. You walk into that barn and they’re happy that you’re there.”

As she ponders her future in this business, that daily dose of predictability means a lot. Not everyone can go to work in the morning and walk through a doorway their great-great grandfather built.

“We’ve just always done it and I gravitated to it right away,” Renee says. “It’s the only thing I know how to do, I guess. I went to school for it. That’s all I talk about is cows.”

Prairies Before Dairies

According to Broxham’s sources, there’s a belief that within the next few years, 70 to 80 percent of the nation’s dairy products will come from megafarms milking tens of thousands of cows. That presents less economic incentive to truck milk from small family farms. Plus, developers have paid farmers high prices for their land.

Where the public consciousness has traditionally seen this as agriculture and development vying for the same land, a third contender has come into view: open-space preservation and prairie restoration. Before settlers arrived, Illinois was 99 percent prairie. Today it’s less than 0.2 percent.

“There are instances when lightning struck in Rockford and the prairie burned to the Fox River before it burned out,” says Aubrey Neville, a retired dairy executive who is restoring natural prairie on 5 acres of his land in Campton Hills. He’s been removing nonnative trees and plants, leaving space for long-dormant native species like bloodroot and mayapple to re-emerge.

As farms come up for sale, conservation entities are trying to protect ecologically significant areas, especially in stream corridors and along the Fox River they feed.

“Half the people in Kane County get their drinking water out of the Fox River,” says Bill Briska, president of the Elgin Area Historical Society. “It’s important to save those recharge areas and streams from development, infiltration, pollution.”

To help farmers contend with the incentive to sell to developers, Kane County has been purchasing development rights in strategic areas. The “Dairies to Prairies” film highlights that effort.

“The farmer can cash in on the increased value of their land if they promise to never sell it into development,” Broxham says. “And they can stay on the land. It helps farms stay in business, so we don’t lose our agricultural heritage.”

Even where the farms and prairies are long gone, their stories could mean a lot for the area’s vitality by helping suburban subdivision residents to better appreciate their land.

“We hope that they have some connection to the land and the people who settled this land, so they feel they’re part of a larger community,” Broxham says. “And when you feel like you’re connected and there’s some heritage to this place, then you are more likely to get involved.”