At the mention of varicose veins, many people tend to shrug and dismiss the subject. After all, their onset is considered part of the natural aging process. Yes, they’re unsightly. Yes, people with varicose veins might need to wear support socks or hose. No big deal, right? Wrong.

Picture the heart as a pulsing, hard-working city. Arteries fan out from the heart like highways, transporting vital nutrition and oxygen to every part of the body. It is the veins’ job to ship the depleted blood back to the heart and lungs for the next load of life-sustaining nourishment. Any obstruction in this complex “freight” system affects the entire body. And varicose veins are a major roadblock that can bring the flow to a screeching halt.

Varicose veins are caused by a persistent, progressive disease called chronic venous insufficiency, in which the valves of veins (most often in feet and legs) malfunction, causing blood to pool, which in turn stretches and hardens the veins. While the only outward symptom might be the seemingly superficial spider and reticular veins, the condition may have already entrenched itself deep in the patient’s legs. The rope-like, hardened veins that mar the legs’ surface are indicators of advanced disease. Venous stasis, a purplish skin discoloration, develops, which can lead to painful ulcers that are difficult to heal.

No one knows exactly why varicose veins affect about one out of every two Americans over the age of 50. But they can occur in teenagers, also, and there appears to be no relationship between ethnic groups and the condition. Between 60 and 65 percent of patients diagnosed with varicose veins are women; 35 to 40 percent are men.

Medical specialists suspect that heredity, obesity, pregnancy and leg trauma, as well as professions requiring workers to stand for long hours, may initiate their onset. Symptoms may include fatigue, a feeling in the legs of heaviness, aching and burning, throbbing, itching, cramping and restless leg syndrome, occurring alone or in tandem.

Because varicose veins aren’t always painful, they have long been considered a cosmetic condition, but if left untreated, they can virtually disable sufferers. Aside from inhibiting the ability to walk, the condition limits other normal activities, such as riding in a car for long periods or flying long distances, robbing patients of a wholesome feeling of wellness, and eroding their quality of life.

If anyone was more than ready to appreciate the advances in varicose vein therapy, it was Dr. Rimas Gilvydis. The interventional radiologist was working at Rush University Hospital in Chicago when the first breakthrough in varicose vein treatments, VNUS (called Venus) was introduced in 2001. Gilvydis says he personally developed varicose veins while still in his teens, and the condition adversely affected his ability to work.

“I couldn’t stand up for the whole day,” Gilvydis explains. “I felt a tremendous amount of discomfort, fullness and pain at the end of the day. I had varicose veins in both legs. Patients with both legs involved have no idea of what normal feels like.”

After undergoing VNUS treatment himself, Gilvydis was sold on the minimally-invasive therapy. In 2004, he opened Northern Illinois Vein Clinic at 1340 Charles St. in Rockford, Ill., after performing the procedures at Rockford’s SwedishAmerican Hospital’s catheter laboratory for several years. By this time, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) was considered the best new therapy for varicose veins.

“If you envision veins as leaky tanker trucks, you understand that only part of the blood is being returned to the heart and lungs,” Gilvydis says. “At the same time, the leaks create unhealthy back-ups and congestion. My job is to seal as many of those leaky valves as I can, because if varicose veins are left untreated, the disease progresses, causing pain, swelling and more damage, such as discoloration and ulcers. The disease can’t be cured, but I can rid a patient of the bad veins they have at this point.”

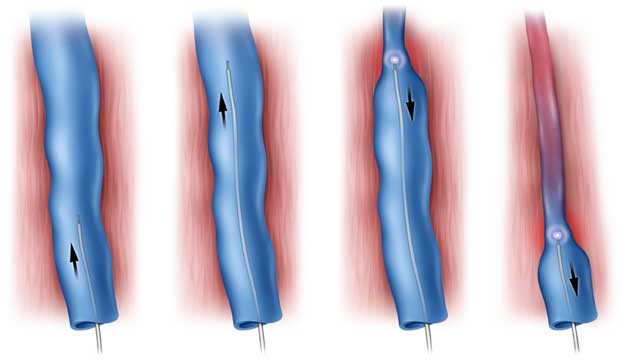

EVLA is the latest advancement in varicose vein treatment. The first breakthrough involved VNUS, the use of a catheter inserted into the affected vein. Intense heat is applied to collapse and shrink the collagen within the walls of the vein, thus closing it off. Gilvydis says he prefers EVLA, because it uses a smaller and less cumbersome devise.

Both of these innovative therapies replaced stripping, for many decades the only method by which varicose veins were treated. As its name implies, stripping is a procedure in which surgeons remove the afflicted veins, without being able to see exactly what they are doing.

Not only is this treatment very painful, but it is invasive and requires up to two months’ recovery. In contrast, EVLA is minimally invasive; recovery time is measured in days and outcomes are better.

EVLA therapy starts with a consultation at the clinic. Gilvydis does an ultrasound evaluation of all the veins in the patient’s legs, to map out and locate damaged valves and leaky points – the “main culprits” that cause varicose veins. The mapping procedure usually lasts between 45 and 60 minutes, after which, Gilvydis submits his findings and photographic evidence of need to the patient’s insurance carrier. When the letter of authorization arrives, the clinic notifies the patient and schedules the first procedure.

“EVLA is used to close the largest varicose veins, the trunk veins and some of the bigger branches,” Gilvydis says. “After local anesthesia, a tiny incision is made, and the laser catheter is fed through the affected vein. Within the cath is a laser fiber which emits energy that seals and shrinks the vein wall. The treatment takes between 60 and 90 minutes. I can attest personally that patients feel nothing after the numbing procedure.”

Depending on an individual patient’s diagnosis, one or more follow-up therapies may be recommended. Gilvydis does ultrasound-guided foam therapy to smaller veins which have separated from the larger veins after the initial procedure. Sclerosant is injected into the varicose vein branches, causing them to swell, stick together and seal shut. The procedure lasts about 30 minutes and may need to be repeated after three months.

Gilvydis describes the final possible treatment as the “finishing touch.” Light-guided foam sclerotherapy involves injecting a milder form of sclerosant, which closes reticular veins that connect to the visible spider veins on the skin’s surface.

“After the final treatments, all symptoms are gone and healthy blood flow is restored to the legs,” Gilvydis says. “We may recommend cosmetic treatment for external spider veins, depending on their severity. This involves one to four treatments with injected liquid sclerotherapy that last between 30 and 45 minutes each.”

Asked when patients should seek EVLA therapy, Gilvydis stresses the sooner the better. Among the positive benefits of undergoing these treatments is the potential discovery of peripheral artery disease (PAD).

“When I map the patient’s veins during the consultation, I screen for PAD,” Gilvydis says. “I won’t perform EVLA on patients with PAD, because of the poor circulation related to the condition. As an interventional radiologist, I treat PAD first, before I start EVLA therapy.”

Another amazing result of EVLA therapy is the elimination of skin ulcers which can plague varicose vein sufferers. “Ulcer patients are sent to wound care clinics for treatment at least once a week for years,” Gilvydis adds.

“These wounds never really heal, because of the patients’ poor circulation. Treatment helps to relieve swelling and pain, but it leaves patients more or less unable to walk much. About two weeks after EVLA therapy, the ulcers heal completely.”

Gilvydis says he tells his patients to get up and get moving. With healthy blood flow restored to the heart, lungs and legs, and the pain, swelling and other symptoms of varicose veins gone, patients can once again travel, play golf, hike, bike, bowl, walk and get back on the road to active lifestyles. And now that Gilvydis has addressed the serious medical ramifications of varicose veins, he’s expanding his practice to include cosmetic services. The addition will be located immediately next door to the clinic in the same medical building.

“I actually already provide cosmetic therapies for painful and unsightly spider veins, primarily because patients have asked for the procedures,” Gilvydis explains. “Once we expand into the cosmetic arena, we’ll be able to offer the entire gamut of protocols.” ❚